The Sparrow and the Lily

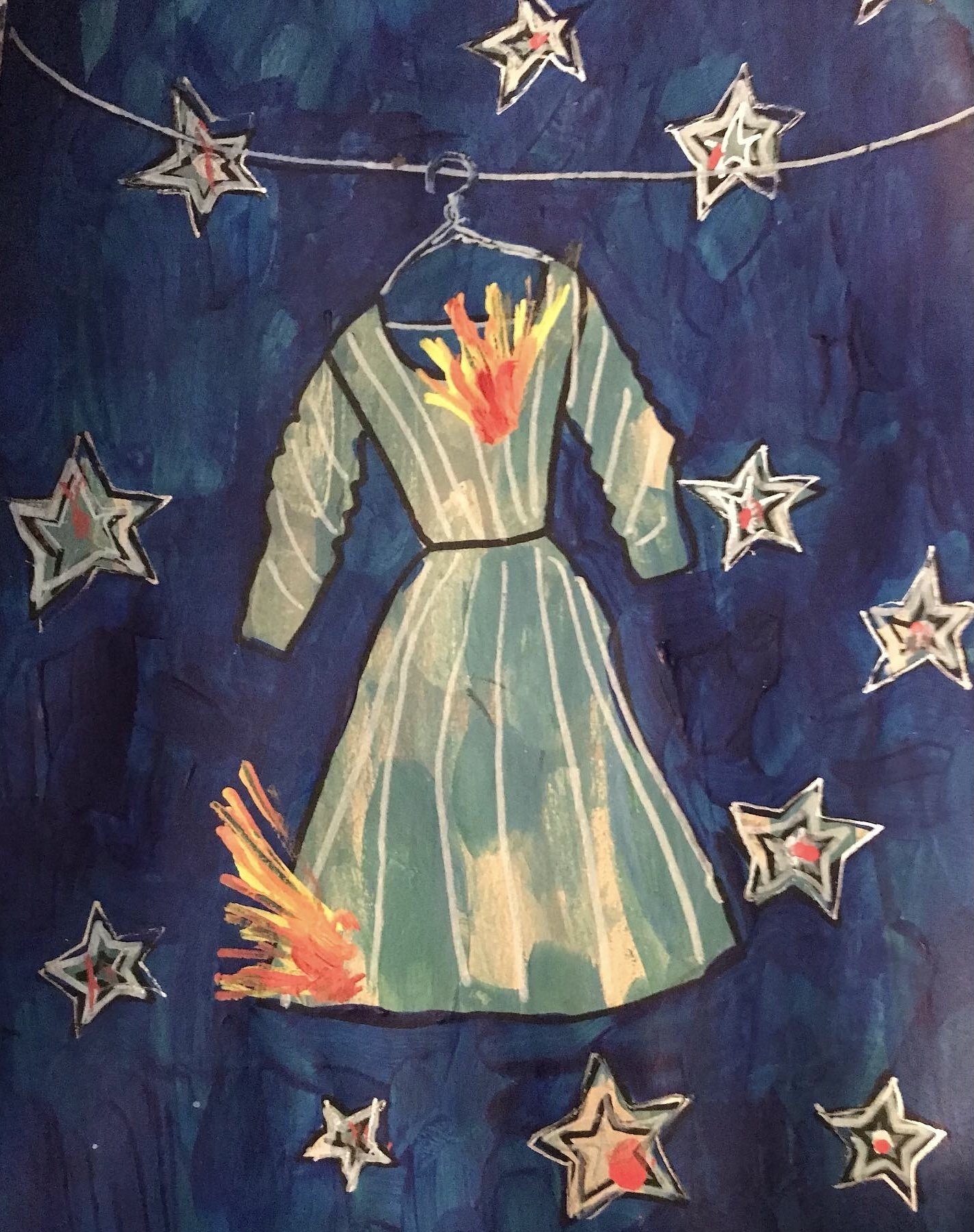

“Untitled” by Rachel Coyne

I was throwing leftover breadcrumbs to our chickens when I heard the trumpet blowing and looked to the eastern skies to see if the Second Coming of Christ was finally upon me. The sky was empty, though, and there was no angel; it was just my cousin, Darby, playing the trumpet next door. She was playing the song, “Smoke on the Water,” and I figured when Jesus made His next physical appearance, He’d have the angels play something a little more serious.

I finished throwing breadcrumbs as the Carolina sun set the tops of the trees on fire. The heat burned my eyes as I tore them away from the sky and back to my house, where Momma was watching Daddy die.

Darby only practiced her trumpet when she was thinking, and whenever she was thinking, she was up to no good, or at least, that was what Momma always said. I was supposed to go back inside once I was done feeding our chickens, but my feet carried me past the tobacco fields and down the wide path to Darby’s house.

***

Darby was sitting on her front porch, lips curled around the mouthpiece of her trumpet, and her long hair was tied up with orange twine, the kind that held hay bales together. She’d been practicing all summer because she was determined to make the high school band this year. She was a rising junior, and she would’ve been able to join her freshman year had she not given a blowjob to the lead trumpet’s boyfriend. Now that the lead trumpet had finally graduated, Darby had a fair shot. She wanted me to join the band, too, now that I was the rising freshman, but I didn’t want to. I didn’t usually tell Darby no—no one did–but Daddy was dying, and Momma was watching, so Darby left me alone and she was nice to me. She was always nice to me, but even nicer than usual.

Darby stood up when she saw me coming up the wide dirt path to her house and removed the trumpet from her lips, smiling.

“Merit!” She waved, her favorite shirt rising up enough to reveal she wasn’t wearing any pants, just a pair of polka-dotted undies. “How’d that sound?”

I smiled. “It sounded good.”

“Just good?”

“It sounded great, Darby,” I said, and I really meant it.

Darby beamed. “That’s what I like to hear.”

Darby’s favorite shirt was the one we got at church camp earlier this summer. It was her favorite shirt because she said it was ironic since she usually sinned the most at church camp. I told Darby almost everyone sinned at church camp; lots of people downed the after-supper cups of blue Jello like shots, or at least how church campers thought someone should take a shot. Darby wasn’t having it, though. She said she won at being a sinner because she found the pastor’s son’s virginity there, and she let him find hers.

I crossed my arms, digging my bitten-down nails into the flesh of my soft bicep. I only released when I felt the half-moons forming. They stung in the fading sunlight.

“Whatcha doing now?” I finally asked.

Darby raised an eyebrow at me, gently setting her trumpet down. “You really wanna know?”

I looked down at her feet, and when I saw that they were dusty, I remembered I envied her. Momma wouldn’t let me go barefoot all summer like Aunt Dovey let Darby. Momma made me wear sandals and a hat, and I couldn’t wear shorts. I had a pair of jean ones hidden under my bed, but I didn’t actually wear them. It was fun to imagine, though.

I looked up. Darby’s eyes were bright-dark, just like mine. “You’re going to tell me, anyway.”

She blew a piece of hair out of her face. “Today,” she said, “I’m going to steal the church bell.”

I frowned. “Why’re you going to do that? How are you going to do that?”

“Abel’s going to help me,” she said, leaning over and grabbing her trumpet case. She set it on the wicker rocking chair and started putting her trumpet away. “And I’m going to play ‘His Eye is on the Sparrow’ from the pulpit because I’ve always wanted to do that, and you’re going to go with me and light a candle for your daddy.”

“I’m going to go, too?”

“Of course, you are, Merit.”

I looked at my feet. My sandals were too small. The orange nail polish on my toes was cracked and fading. “Why do I need to light a candle for Daddy?”

“I think the Catholics do it for people who are sick,” Darby replied, snapping her trumpet case shut. She put her hands on her hips. “It might help, you know. It can’t hurt, anyway. We don’t have to talk about it.”

I nodded. She knew I didn’t like to talk about it.

Darby waved a hand. “Look, I’m going to get dressed, and then we should head on. I’ll get a flashlight, alright?”

I wiggled my toes, and the faded, chipped golden buckle on my sandals ignited, momentarily blinding me. I thought of Saul-turned-Paul and wondered if maybe I’d become one of the greatest missionaries there ever was, but gave up the idea moments later when no scales fell from my eyes. I looked at Darby again.

“Alright.”

***

I didn’t know how to ride a bicycle, which was okay because I didn’t have one, but it did mean that Darby and I had to walk to the church, which was okay because Darby didn’t know how to ride a bicycle either, and she didn’t have one. It was a long walk. We passed the tobacco fields that separated my house from Darby’s, the cotton fields that separated the outskirts of town to the center, and the two separate pastures of goats and sheep that were next to the church. It was a long walk, and Aunt Dovey, who was Momma’s sister, would let Darby do anything, that was what Momma always said.

Momma knew I was with Darby, I went home long enough to tell her, but she was busy watching Daddy die, so she didn’t ask me any questions when I told her we were going to church. She made me put on a new dress, though, a sundress that I thought was too sheer during the day. The sunset turned my dress golden, and Darby said it brought out my eyes. She mentioned again, the third time just that week, that Abel had a younger brother, Thaddeus, who thought I was pretty. I didn’t think anything of Thaddeus, other than thinking how I admired the way he always began his prayers during Sunday School by saying Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am chief.

Darby knew everything. Except for one thing, and I hated that I knew the One Thing and she didn’t. I couldn’t tell her either, because I’d promised I never would. I swore to God and everything, and I figured if I told her, then I’d get smited like Sodom and Gomorrah. I dreamed about that sometimes, standing in the middle of the dusty tobacco field and a giant fireball coming out of the eastern sky and disintegrating me. Sometimes, when I woke up from that dream, I was disappointed, but only until I remembered wanting to kill yourself was a sin, too. I didn’t really want to die, just sometimes, I wished I didn’t exist.

By the time we reached the church, the moon was out and the half-crescents on my arm had faded along with the sun. Darby had taken her favorite shirt, the one we got from church camp, off and was wearing a tank top and jean shorts, the same kind I kept hidden under my bed. She stood up straighter when we saw Abel leaning against the doorframe of the church, and he smiled at her when he saw her because he loved her. I think Abel had loved Darby for a long time, even before they found each other’s virginity at church camp.

“Hey, you,” Darby said with a grin, handing me the trumpet case and throwing her arms around his neck. She looked over her shoulder at me, and then pulled herself up, whispering something in Abel’s ear. He turned red, and I looked at my feet. Blisters were forming on the sides of my foot where my shoes pinched. One was full of blood.

“Alright, Darby,” Abel said after a minute, smiling. He put his hands on her hips, holding on even after she’d removed her arms from his neck. He looked at me over Darby’s head. “Hey, Merit. How’s your daddy?”

I shrugged. “Still dying, I guess.”

Abel’s smile disappeared. “Oh. I’m sorry.”

“He might be alright,” Darby said, turning around to look at me. “You know, the doctor said he might still pull through, even without an arm. He survived, Merit. You don’t survive something like that just to die.” She turned back to Abel. “She’s going to light the candles for her daddy, the ones on the communion table, and she’s going to pray for him, too.”

“I thought I was just going to light a candle,” I said.

Darby rolled her eyes. “Well, you have to pray for him, too, if you want it to work. I mean, what else are you going to do, Merit? Just watch the candle burn? That won’t help anything.” She let out a breath. “Alright. Abel. You got the key?”

Abel nodded and pulled the church key out of his pocket, opening the doors to the vestibule. “I got it,” he said, “just don’t tell my daddy I let you in. It’s only for emergencies.”

We used to not lock the church doors, but then somebody started stealing money from the offering plates. Then, somebody vandalized the church. They wrote vagina on the nursery wall.

“This is an emergency,” Darby said, taking back her trumpet case and waltzing in. She smiled at me, and then she smiled at Abel. “Let’s take the bell first.”

I started to sweat, and a vision flashed through my mind’s eye of Darby climbing up to the steeple of the church and pulling the bell down just to slip and throw herself down. I thought about how Satan told Jesus the Angels would save Him if He threw Himself off the pinnacle of the Temple of Jerusalem. Would the Angels save Darby, too? Probably not. Jesus never actually fell.

“I hate that thing,” Abel said, taking a stride ahead of her. “Daddy puts it in the Sunday School office.”

The River of Peace flowed through me when I realized that Darby was talking about the choir’s hand bell they rang near the end of Sunday School every week to let everyone know there was only five minutes left. It was a tradition, and everyone hated that bell and how loud it was, and how it echoed down the hall long after its first ring, but only Darby admitted it.

“The bell is an antique,” I said as the River of Peace dammed up with worry. “It’s over a hundred years old, Darby. They’ve been using that bell for over a hundred years.”

Darby let out a huff. “Well, we can just hide it, then. How about that, Abel?”

Abel nodded. “I can live with that.”

“Alright, then.” Darby pointed to the sanctuary. “Merit, why don’t you go ahead and get started with your candle and prayer. Abel and I’ll meet you there in a few minutes. You ain’t scared, are you?”

“No, I ain’t scared.”

I wasn’t scared of anything. I was just scared of everything.

“Good.” She held out a hand for Abel. “Come on, let’s go get that damn bell.”

“It is a damn bell,” Abel agreed, taking her hand and looking at her. He smiled as they walked down the hall. “If my parents heard me curse in church, they’d send me off to Oklahoma to live with my grandmother.”

Darby smiled back at him. “Oklahoma sounds even more boring than North Carolina.”

“It is.”

I watched them until they turned the corner and then stared at the double doors leading into the sanctuary for a few minutes before walking in. I could’ve turned the lights on, I knew where they were at, but I didn’t. The sanctuary was dark, much darker than it was outside, and the only light was coming in through the stained glass. The orange shag carpet glowed in multicolor as the Story of God danced across the room, and I could almost hear the saints at the finish line, calling me, telling me I was almost there. I closed my ears to them, though, once I realized I was overhearing the ones calling for Daddy. I didn’t want him to die, and I didn’t want to die either, even though sometimes I wished I didn’t exist.

I stepped up to the cedarwood communion table in front of the pulpit and picked up the box of matches that was always sitting there. Nobody ever replaced the matches, but we never ran out, and I knew why. It was our fish; it was our bread; there was always more than enough. That was why I didn’t feel guilty when I had to try three different matches just to get one to light.

Once the fire ignited on the red bulb of the tiny wooden stick, I pressed its tip to the tallest candlestick on the left side. I lit the candle on the right, too, for good measure. The clear white wax dripped down both of the candles at the same speed, tainting the golden holder. I got on my knees in front of them, preparing to pray as the rough carpet branded shapes into the flesh of my knee, but no words came out, so I let my heart talk. I was still enough I could hear it breaking, and right before I started to cry, I stood up and sat on the front pew.

The Story of God was still dancing across the room as I closed my eyes. I heard the choir singing in the ear of my mind, and as they sang, I saw myself walking to the front of the aisle the day after Daddy’s accident. It was weeks ago or yesterday, I wasn’t sure, but I remembered how each step alternated between being easier and harder than the one before. Everyone’s eyes watched my back, saw through the back of my dress as lukewarm beads of sweat flowed down it, and condemned me for my father’s sins. When I finally reached the front of the church, when Abel’s momma held my hand and Abel’s daddy prayed over me, I thought about Isaac, and wondered if that was how he felt on top of Mount Moriah when he was tied down. I wondered if the rope left burns on his skin, or if he had nightmares about the way the cold-hot-warm-cool stones felt on his back as he laid there and watched his daddy raise the knife.

I wondered if Isaac was like me and didn’t hear a word his daddy said, just like I didn’t hear a word Abel’s daddy said. All I heard was the choir, the crescendo ringing in my ears as I prayed to myself. I prayed for Daddy to get better, and I prayed that I would forget the way Daddy screamed when the car swerved, the way his body soared on wings of eagles over the cattails by the ditch. I was the one who found him, bloody and pale, resembling the fertilized eggs that I cracked into the skillet by accident one morning. Daddy’s blood bubbled in the ditch water the same way the amniotic fluid bubbled on the cast-iron, and both times it was Momma who heard my screams and came running. Both times, she told me to close my eyes. Both times, she reminded me that life and death were not opposites. They were intertwined like day and night were, held together by sunsets and sunrises; they were intertwined like hot and cold were, chasing each other until something entirely new and beautiful and destructive was formed. To be alive is to be pre-dead, and to be dead is to have been alive, or at least that was what Momma always said. I prayed I would forget that, just like I prayed I would forget the accident; just like I prayed I would forget it wasn’t really an accident at all. Wisdom is grief.

I sat on the front pew for a long time, probably a lot longer than it felt, before Darby and Abel came bounding into the sanctuary, smiling and holding hands. Darby had her hair tied back again with her orange twine, the kind that tied hay bales together, and Abel didn’t look as nervous about breaking into church. Darby still had her trumpet case, and she sat down next to me, opening it up before saying anything at all.

“You done?” she asked finally. Her eyebrow raised. “Are you alright, Merit?”

I nodded. “Where’d you hide the bell?”

“In the Christmas decorations,” Darby replied, wiping the mouthpiece of her trumpet off. “They’ll never look there.”

“At least not until Christmas,” Abel remarked, sitting down on her other side.

“We’ll move it again, then.”

Abel grinned. “Daddy doesn’t even like that bell,” he said, looking at me and then Darby. “He’d probably even thank us for getting rid of it.”

Darby rubbed her red knees, but the imprint of the carpet from the third grade Sunday school classroom remained. “He’s the pastor. He could get rid of that damn bell if he wanted to. He’s probably just scared of what people would say, especially the old people. They never want to change anything, even if changing something would be better.”

“He’s scared of getting fired,” Abel said, leaning back and putting his hands behind his head. “Momma said he ought to be more scared of God… and her.”

“Your momma is a wise woman,” Darby said, standing up and taking a deep breath. She stepped up to the pulpit and positioned the trumpet at her lips. “Are you ready?”

I didn’t really want her to play her trumpet. I wasn’t in the mood.

“Go ahead,” I said.

“Let’s hear it,” Abel said.

Darby started to play, and I realized I never blew the candles out. The notes from Darby’s trumpet tried to rise above the flames, but the fire only grew. I closed my eyes again, trying to remember the words in my ears as her trumpet sounded.

Why should I feel discouraged

Why should the shadows come

Why should my heart feel lonely

And long for heaven and home.

Daddy was a liar. He lied and told me all the time that, when I grew up, I could be whatever I wanted to be, when all I wanted to be was anything but myself. He lied and told me that stars were holes God cut in the sky so the saints of Heaven could watch over us as we slept. He lied and told me that he was going to Abel’s daddy’s house to look for their bird dog when I knew he was going to go into their cellar to play cards. I knew it, but Momma didn’t, because when I told her, she didn’t believe me, so she didn’t know it. Momma thought I was a liar.

When Jesus is my portion

A constant friend is He

His eye is on the sparrow

And I know He watches over me.

All the men at church played cards, but not all the men had bad luck and no way to pay off their debts. Not all the men owed The House more money than they made in a year. Not all the men knew that Abel’s daddy was not really afraid of God. Not all men threaten to tell the whole community a pastor’s sins, of the money earned and lost, of the temptations bought and sold, of the light and dark that chased each other around and around and around. Not all men get hit by a car and survive it, especially when they weren’t supposed to. That was just my Daddy; lying in his bed, dying as infection spread throughout his body, as he sweated through his sheets, and cried out to God to save his mortal soul because the doctors told him to go home and be comfortable, because it was too late, and all that could save him now was a miracle. That wasn’t the way all men were, that was just my Daddy.

His eye is on the sparrow

And I know He watches me.

Daddy was a liar, but he always told the truth. He told the truth even when he was lying. It was only when he was lying. He thought I was Judgment, and as he lay in that ditch, he lied and told the truth about everything. He told me that when Aunt Dovey and Uncle Humphrey couldn’t have a baby, he and Momma helped them. He told me that they helped each other because he and Momma were too young and they weren’t ready yet, and Aunt Dovey and Uncle Humphrey were old, and they were ready. He told me he didn’t want to, but Momma did, and begged me never to tell myself or anyone else that I wasn’t their first fruits. Daddy thought I was Judgment, but I wasn’t, and I wished that if someone was going to die, it would be me, and not him. Not because I wanted to die, but because I wanted him to live. I’d been Chosen once, but it didn’t seem fair for me to be Chosen again.

I sing because I'm happy

I sing because I'm free

His eye is on the sparrow

And I know He watches me.

I wasn’t angry with God. I think everyone thought I was, but I wasn’t. I was too scared to be angry at God even if I wanted to, but I didn’t want to. I wasn’t angry with anybody, not even Abel’s daddy, not really, because I was scared of him, too. I was scared of myself.

I stopped listening to Darby, and the ear in my mind, and I started to pray, hoping I’d do it so well, I’d sweat blood, or maybe God would sweep me up in a chariot of fire just like He did Elijah. I didn’t really want to die, but sometimes, I wished I didn’t exist.

Once I finished, Darby screamed, and I looked up. One of the candles on the cedarwood communion table had fallen over, and the table was on fire. The finish on the cedarwood table glistened with the red, orange, and golden flames, and it didn’t burn.

I stared at it, transfixed and unblinking, despite Darby’s screams and Abel’s shouts, and kicked off my shoes like Moses did. The golden buckle caught in the light of the fire as it flew behind me, and the orange nail polish on my toes was cracked and fading, but it didn’t matter. Darby’s theory about trying the Catholic way was right, and I knew Saint Teresa was jealous.

I dropped to my knees, and the impact made me blink, and it was only then that the cedarwood communion table began to catch. Darby’s screams were present once again in my ears as she ran back and forth from the baptismal pool, throwing water on the fire yet only growing it. Her trumpet was thrown across the altar, her sacrifice, and I didn’t see Abel. I didn’t see Abel until he came back with a fire extinguisher. Darby yelled at me to get out of the way, but I didn’t move. Dust settled on my eyelashes, and I waited for the fourth person to come walk around the fire with us. It wasn’t until Abel grabbed the back of my dress and yanked me down, spraying the cedarwood communion table, that I let out the breath I was holding and shivered.

Once the fire was out, Darby ran over to Abel and hugged him, and then hugged me, and then started to cry.

I stood there, unmoving, overwhelmed, because the saints stopped singing and I knew Daddy would be okay. I knew it. I could see him in the eye of my mind, his fever breaking the moment the sun shone through the moon, baptizing the tobacco fields around our house in fire and light. I could see him, fever broken, left arm missing, having offended him, sitting up in bed and asking for water. I could see him as Darby, Abel, and I left the sanctuary after wiping away scars on wood and opening windows to release smoke-stained air. I could see Momma crying over him, weeping and wishing she had alabaster oil to anoint his head. I saw myself, standing in the middle of the Story of God, and watching it unfold around me; I saw myself, a lily, not toiling or spinning in the field, but with rain falling softly on my petals, strengthening my roots.

The dawning moon illuminated the Story of God as we left the sanctuary, the window of resurrection, and it danced on the orange shag carpet. I tried to stare, but Darby grabbed my hand and pulled me away, asking me why I hadn’t tried to stop the fire. I didn’t answer. Her wide eyes were closed from the inside out, and I had no mud to put on them.

about the author

M. Holladay Brantley is a graduate student in the MFA creative writing program at NC State in Raleigh, NC. Her writing has been featured in Windhover Literary Magazine and she was a finalist for the James Hurst Fiction Prize for fiction in 2020, 2021, and 2022. You can find her on instagram @m.holladay.brantley

about the artist

Rachel Coyne is a writer and painter from Lindstrom, MN.